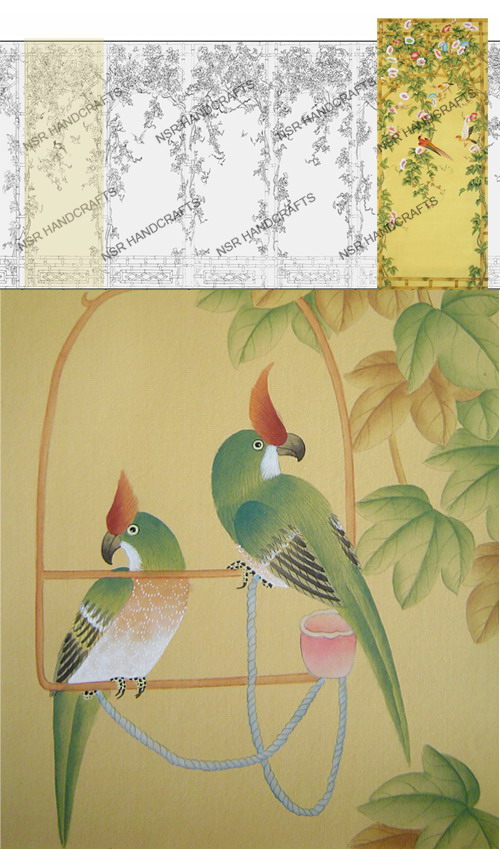

Small pagodas appeared on chimneypieces and full-sized ones in gardens. Kew has a magnificent garden pagoda designed by Sir William Chambers, a replica of which was built in Munich's Englischer Garten. Though the rise of a more serious approach in Neoclassicism from the 1770s onward tended to replace Oriental inspired designs, at the height of Regency "Grecian" furnishings, the Prince Regent came down with a case of Brighton Pavilion, and Chamberlain's Worcester china manufactory imitated gaudy "Imari" wares. While classical styles reigned in the parade rooms, upscale houses, from Badminton House (where the "Chinese Bedroom" was furnished by William and John Linnell, ca 1754) and Nostell Priory to Casa Loma in Toronto, sometimes feature an entire guest room decorated in the chinoiserie style, complete with Chinese-styled bed, phoenix-themed wallpaper, and china. Later exoticisms added imaginary Turkish themes, where a "diwan" became a sofa. Various European monarchs, such as Louis XV of France, gave special favor to Chinoiserie, as it blended well with the rococo style. Entire rooms, such as those at Château de Chantilly, were painted with Chinoiserie compositions, and artists such as Antoine Watteau and others brought expert craftsmanship to the style. Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese taste" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German and Russian palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez near Madrid. The whole Chinese Villages were built in Drottningholm, Sweden and Tsarskoe Selo, Russia. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and china cabinets, especially, were embellished with fretwork glazing and railings, ca 1753 - 70, but sober homages to early Qing scholars' furnishings were also naturalized, as the tang evolved into a mid-Georgian side table and squared slat-back armchairs suited English gentlemen as well as Chinese scholars. Not every adaptation of Chinese design principles falls within mainstream "chinoiserie." Chinoiserie media included "japanned" ware imitations of lacquer and painted tin (tôle) ware that imitated japanning, early painted wallpapers in sheets, after engravings by Jean-Baptiste Pillement, and ceramic figurines and table ornaments. Earliest hints of Chinoiserie appear in the early 17th century, in the arts of the nations with active East India Companies, Holland and England, then by mid-17th century, in Portugal as well. Tin-glazed pottery (see delftware) made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine blue-and-white Ming decoration from the early 17th century. After a book by Johan Nieuhof was published the 150 pictures encouraged chinoiserie, and became especially popular in the 18th century. Early ceramic wares at Meissen and other centers of true porcelain naturally imitated Chinese shapes for dishes, vases and tea wares. From the Renaissance to the 18th century Western designers attempted to imitate the technical sophistication of Chinese ceramics with only partial success. Direct imitation of Chinese designs in faience began in the late 17th century, was carried into European porcelain production, most naturally in tea wares, and peaked in the wave of rococo Chinoiserie (ca. 1740-1770). Chinoiserie is a mixture of Eastern and Western stylistic elements for both the decoration and shape. Chinoiserie, a French term, signifying "Chinese-esque", and pronounced [ʃinwazʁi]) refers to a recurring theme in European artistic styles since the seventeenth century, which reflect Chinese artistic influences. It is characterized by the use of fanciful imagery of an imaginary China, by asymmetry in format and whimsical contrasts of scale, and by the attempts to imitate Chinese porcelain and the use of lacquerlike materials and decoration. The term is also used in literary criticism to describe a mannered "Chinese-esque" style of writing, such as that employed by Ernest Bramah in his Kai Lung stories, Barry Hughart in his Master Li & Number Ten Ox novels and Stephen Marley in his Chia Black Dragon series.

0 comments:

Post a Comment